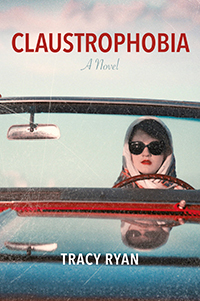

Tracy Ryan Claustrophobia (Transit Lounge, 2014)

My friend Tracy Ryan’s new novel, Claustrophobia, was published recently by Transit Lounge. Set in Perth, it’s a literary thriller about a woman’s obsession with her husband, Derrick’s ex-lover, Kathleen. The claustrophobia of the title is an apt description of the feel of the novel. We’re constrained within the narrative viewpoint of Pen and her narrow, obsessive world. Her marriage is claustrophobic, too, the jealousies and social isolation fueling her behavior. The clichés in which Pen talks and coats her world hint at a darker side constrained within, and it’s this side of her which is gradually revealed.

Pacing is important to the thriller, and in this novel it’s just right, building up tension slowly and, for the reader, unbearably, knowing something must break. The plot opens with an inciting incident of Pen uncovering an undelivered letter from Derrick to Kathleen, and deciding to open it and read it. From here, this initial decision to keep a secret in her marriage in retaliation snowballs expertly with each chapter.

I’m left at the end unsure of how to judge the characters; this ambiguity is probably part of the novel’s psychological accomplishment. Pen is an unsettling protagonist to live with for 240 pages. The positive spin on her provided by one of the other characters is that she’s intelligent and passionate, but crippled by low self-esteem. Yet as with people in real life, the characters around her don’t know the level of neurosis and obsession percolating behind her façade. Derrick, her husband, truly is too controlling, and can be seen to have helped cause Pen’s madness; yet he is a somewhat more balanced and grounded person than Pen. Kathleen is the most sympathetic of the major characters, an articulate and generous academic who lives life to the full—and yet has her own obsessiveness which emerges late in the novel.

The novel evokes Perth so very well, from suburban life in the hills, to the hallways and cafes of UWA, as well as the bush town of Pemberton. There are too few novels set in Perth, and this one is convincingly grounded in it. It’s possible to loosely associate it with the crime genre, and suggest that with the work of David Whish-Wilson and Felicity Young it begins to map out Perth as an increasingly plausible setting for crime fiction.

On the subject of genre, the characters discuss the novels of Patricia Highsmith and Georges Simenon, perhaps a case of the novel wearing its influences proudly. These are the right reference points for a contemporary novel in the tradition of these two writers, with the fresh setting of Perth.