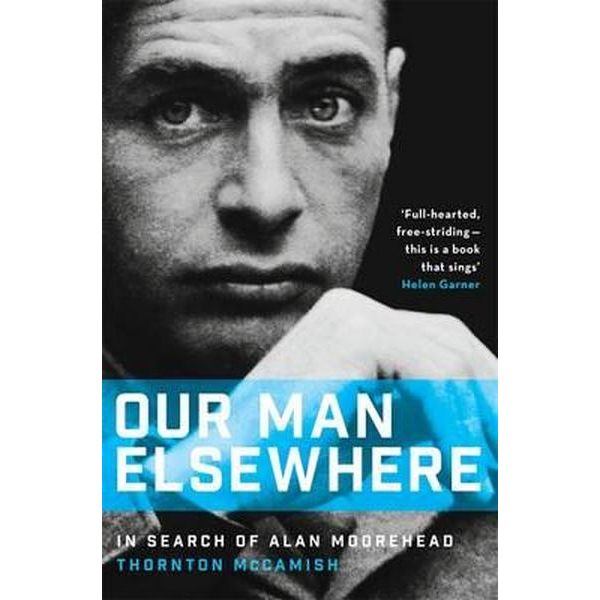

For the second year, I’m working on an annual bibliography and introduction to Australian literature with my supervisor and another co-author for the Journal of Commonwealth Literature. My focus is on non-fiction. I was surprised to find that in 2016 there were just five Australian literary biographies published, at least by our reckoning. Three of them came from UWA Publishing; the other two were both about mid-century middlebrow writers – Paul Brickhill (The Great Escape) and Alan Moorehead. The reviews for the biography of Moorehead (1910-1983) – Thornton McCamish’s Our Man Elsewhere: In Search of Alan Moorehead (Black Inc) – were so glowing about the writing itself that I just had to read it, despite barely having heard of Moorehead.

It truly is an excellent biography. It is a biographical quest as McCamish begins by describing the fever of obsession with Moorehead that came over him and asks why Australia’s most famous writer in the US and Britain in the 1960s has been so forgotten fifty years later. Some of the finest reflections on biography occur within biographical quests and McCamish’s were delightful. His account of looking through Moorehead’s papers at the National Library of Australia described my own experiences there so perfectly. In another scene, he captures so well the sense of the past, the thrill, the anxiety, and the prosaic elements of trying to find Moorehead’s house while on holiday in Italy with his wife and small children. Some quotes:

There isn’t much logic to the in-the-footsteps method. My idea was that if I followed the thread linking Moorehead’s words to the places where he wrote them, I might, with some intuitive effort, some narrowing of the eyes, get a fuller imaginative sense of what his world felt like. (124)

It was unsettling to meet the nieces. Years of document-sifting and note-taking hadn’t prepared me for the warmth of living memory. (148)

The photo of Moorehead with Churchill posed a question, one that is implicit in any book about a writer, but which I have managed to ignore till now. Was the life more interesting than the work? Or more specifically: had the life aged better than the books had? (202)

My Moorehead was constructed from the printed word, mostly, and my own preoccupations. But the actual man existed most truly in what people could remember of him; in what remained in fragile containers of memory. (206)

The focus, though, is on Moorehead’s life itself more than McCamish’s quest. McCamish describes the World War Two years in the most detail, the time when Moorehead turned his war journalism into a bestselling trilogy that made his name as a writer. He had a full, exciting life in the decades which followed, and yet McCamish captures so well an ennui always lurking in the background. It is a relatively short biography for an entire life at 351 pages, and the elements not pursued at length are his family and romantic lives. Moorehead’s wife, Lucy, is glimpsed as a fascinating character in her own right – crucial to his success – and we are only given limited insight into her feelings about his constant infidelity and long absences. With their children still alive, it would have been an area McCamish had to tread carefully.

This is a biography which gives a vivid sense of life and culture in the mid-twentieth century. It reflects in an indirect but profound way on what makes life meaningful and how the past is present – or not – today. It didn’t leave me with a strong desire to read Moorehead’s work but it did leave me with a strong desire to read whatever book McCamish writes next.