Tags

I came across Griff Watkins (1930-1969) for the first time in The Fremantle Press Anthology of WA Poetry, edited by John Kinsella and Tracy Ryan. It was a wonderful poem about a Perth heatwave in the 1960s which reminded me of W.H. Auden. The snippet of his biography intrigued me: he drowned himself in the Swan River at Claremont a couple of years after the publication of his debut novel, The Pleasure Bird. After that, I kept on running into him. I found out he’d taught at Collie Senior High School in the South-West, where I’d gone to school in the 1990s. I was visiting Murdoch University’s Special Collections and saw his papers on display. I read his novel and I loved it. I wondered if it would be possible to write a whole book about my quest for Griff, a book about posthumous obscurity, the more typical writerly life of moderate success and many failures, the hauntings of a literary ghost in Perth. But there wasn’t enough material and there wouldn’t be enough interest.

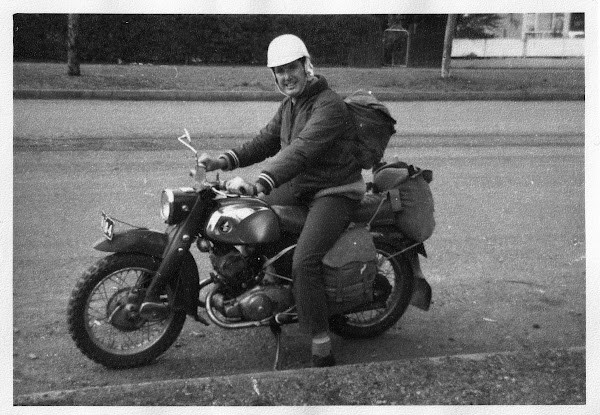

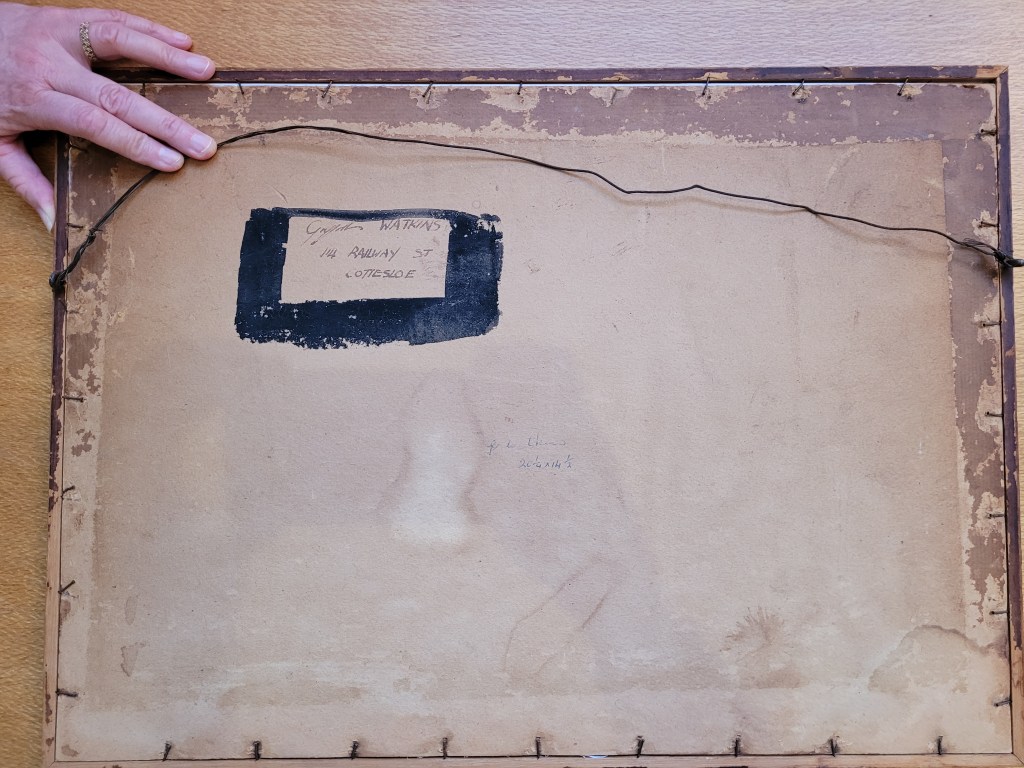

I was thinking of abandoning the project altogether when a PhD student named Mary asked me what I was working on. It turned out her mother, Betty, now in her late 90s, had taught with Griff in Collie. (Coincidentally, Mary’s sister, Pip, was also my mentee in the Four Centres Writing Program.) It was a sign. I interviewed Betty over the phone; she remembered Griff so sharply and insightfully. She had the beautiful photo, above, of Griff on a motorbike from his last visit in Kalgoorlie, and this painting of his (below) he had given her as a wedding present. The scale of my piece shifted: I would tell of my quest for Griff in a single creative non-fiction essay. It was published last year in Westerly 69.1 – my great achievement of 2024!

Some postscripts:

Mary read the piece to Betty, and said she enjoyed it. I was sad to hear of Betty’s death soon after.

I found out after I’d published that my great uncle, John Stanlake, going strong at 94 and an exact contemporary of Griff’s, had known him at Claremont Teachers’ College. I think the connections would keep piling up the longer I spent with Griff.

You can purchase Westerly 69.1 here. And you can read the manuscript version of ‘A Memorial Trail for Griff Watkins’ below.

A Memorial Trail for Griff Watkins

This is a memorial trail for Griffith Watkins (1930-1969). The trail is marked only in my mind. It works like this: when I go past one of these places, I think of him. He is a forgotten chronicler of Perth in the 1960s, a promising writer who tried to find meaning and beauty in the land between the ocean and the river. It’s often the unfamous writers who are more representative of what it means to be one. The ambitions, the struggles, the small victories, the imperfectly realised visions of the world they left us. But it is more than that too. My paths keep crossing with his paths. There are too many associations and connections now. He haunts me and so I must lay out his memorial trail as a way of remembering him.

1. The Pleasure Bird

Copies of Griff’s only published novel are spread throughout the world. There are fifty-three listed on Worldcat, distributed all around Australia along with a fair number in the UK and North America. Abebooks has six copies listed for sale, all at a little less than the price of a new hardcover. If you spot one on a shelf in a library or a second-hand bookshop, you have found yourself at the beginning of the Griff Watkins Memorial Trail.

Brenton bursts from the pages of The Pleasure Bird; he is at war with the sleepy Perth of the 1960s. He’s a man of action, a boxer and a motorbike rider, an artist and a teacher, a philosopher and a lover. He has sworn vengeance on the man who killed his brother in the boxing ring, but his quest is complicated when he kills his best friend in a car accident and takes solace in the arms of his friend’s widow. In one passage, Brenton takes her to see the titular painting, his finest work, which he deeply regrets selling to a restauranteur. The Pleasure Bird is a constantly surprising novel, picaresque in Brenton’s encounters with minor characters, like the philosophising gravedigger and the friendly priest he gives a lift to on a lonely road. The prose is fresh and unpretentious even as Griff engages with big questions of art and meaning. The novel always carries me along with its exuberance and sincerity, and in its determination to live fully.

The university library copy of The Pleasure Bird has a 1960s punch card still stuck in the back recording the names and dates of thirteen borrowers between 1968 and 1975. A student named Smith borrowed it on 8 September 1969, five days after Griff went missing. There was no rush on the book in the aftermath of his death. Another loan in November, and then it sat on the shelf for over a year, until November 1970. It’s the sort of book that could have a cult following if the author dies young—but it doesn’t.

I buy my own copy online. It used to belong to the Senior Citizens’ Club of Ballarat. A typewritten sticker notes on the front page, ‘Dedicated to former member Mrs Coates 17-4-70’. Perhaps the late Mrs Coates had been an open-minded woman who would have quite enjoyed The Pleasure Bird. Though, if she was a typical member of the generation born during the last years of Queen Victoria’s reign she would have been shocked by this racy story of sex and violence among the youth of Perth. Perhaps it was bought as a bulk order from funds the senior citizens had put up in her memory? I wonder how long the people responsible thought the books dedicated to her might remain in the club’s library. Books have an illusion of permanence.

2. Collie

I drive past the high school with my impatient children in the car. None of the buildings I can see from the road were there in my time, let alone Griff’s. I came to the school in 1994 as a year eight Baptist kid, uneasy among the coal miners’ sons who’d punch me in the arm to try to make me say a swear word. Griff came in 1950, a twenty-year old school monitor, and spent four years in town.

I think of the old part of the school, the English classrooms with their tall ceilings and tattered copies of a class set of Catcher in the Rye stacked in a corner. These rooms led onto a hall with green stage blocks.

I remember long afternoons of theatre studies in the summer heat. A mirror on the wall with an inscription, ‘To the school from the 1969 Prefects’. That part of the school hadn’t changed in decades. I imbibed the same atmosphere as Griff, only it was new when he was there and aging when I knew it. This thought reorientates my memories of Collie. Every angsty teenager takes pride in the illusion that their quest for authenticity is unique. But now I’m glad to find the memories of myself in that place overlaid with Griff’s presence thirty years earlier.

I’m put in touch with Betty Brennan, ninety-seven years old, who taught with Griff at Collie. She boarded with him at Mrs Washer’s place; he had a tiny room at the back of the house. She says he would have manic periods of intense energy, wanting people to play tennis with him at 6am. He was always the life of the party; he’d get everyone’s attention so he could perform with musical instruments he barely knew how to play. He brought joy to people and made them laugh. But, looking back, Betty can see that he was often covering up periods of great distress. Just before Betty left Collie, Griff was engaged to a local woman but when Betty saw him a year or two later, he’d broken it off.

3. Swanbourne

The memorial trail takes me past Griff’s family home. It’s a non-descript brick house behind a high fence right on the railway line. From Griff’s house you can almost see Scotch College on the other side of the railway line, the prestigious private school he attended. The yearbook from 1947 shows him a lance corporal in the cadets, an undistinguished student, a hockey player, the victor in a boxing match.

This is the house Griff returned to when he finished at Collie. He lived with his parents while he worked hard at his job, his studies, and his writing. 1961 was a turning point in his writing career. He won the ANA Short Story Competition, the Weekend Mail Short Story Competition and gained both first and second places in the Toowoomba Poetry Competition. ‘Although I now write an average of fifteen hours a week, this is the first year I have been dedicated,’ he wrote in an unsuccessful application for a scholarship to the Stanford Writing Center in California. ‘I feel that someone actively engaged in creative writing would be able to give Teacher Training College students some vital encouragement in this field at a time when they need it most. There is a frightful waste of talent here. I intend to remain a teacher and to write and attempt to make some contribution to the climate of writing in this state’ (Watkins 1961). His was more than a commitment to staying in Western Australia: he was committed to writing about it too. In 1966, he used his long service leave to research a new novel in Broome and Kalgoorlie, rather than taking a trip to Europe (Jeffery 246).

Closer to home even than the far reaches of Western Australia, he celebrated and remembered the Swanbourne of his childhood, ‘the growling world of my wedding / To river, swamp and sea’. In an unpublished poem called ‘Swanbourne’ he writes, ‘And what the senses say on any walk over / Melon Hill and the brawny dunes beyond / Is sensible and just’. Following in his footsteps, I walk up the steep hill, uncontemplatively, on a sunny Sunday morning and, at the top, the Indian Ocean springs into view. A brass plaque, all in capitals, commemorates the battery observation post which operated from 1936 to 1963. Houses are encroaching, the trees are taller than they would have been in his day—but the ‘brawny dunes’ remain. ‘This place will still be loved’, Griff writes, ‘even when / I am gone to greener pastures’.

Griff would get a shock if he saw Tom Collins House, headquarters of the Fellowship of Australian Writers, at the bottom of Melon Hill. The house was moved from its old location one kilometre to the east in 1996, to make room for West Coast Highway. When Griff joined the fellowship in 1959, he was welcomed as ‘one of the most talented and accomplished younger writers the WA literary scene had produced’ (Kotai-Ewers 233).

4. From Cottesloe Beach to Claremont foreshore

This section of the Griff Watkins Memorial Trail starts at Cottesloe Beach. That’s where his car was found during the school holidays of September 1969. He was last seen alive on Tuesday September 2nd. His mother, Kate, remembers, ‘I sensed something was not right with Griff that day […] He was messing about outside when he suddenly said he was going to see a friend.’ At 4am, she found his bed hadn’t been slept in, and she rang his friend to find he hadn’t come to visit. His car was discovered on Thursday September 4th, with clothing in it. There was a notebook in the car containing the lines:

And if you are fond of me

Regard it as a mild misfortune

Police and friends began searching the sand dunes near the Swanbourne rifle range, the area around Melon Hill he was so fond of. They found nothing; the theory changed: ‘Police believed he could have drowned while swimming off Cottesloe’ (Moran).

On Saturday September 13th, eleven days after Griff went missing, three shearers in their twenties were walking along the Claremont river foreshore. At about 9.15am they stopped at the yacht club jetty, to look at the boats, when they noticed a body floating in one of the pens. The police were called and they dragged it to the shore. It was Griff. He was fully clothed, with a chain around his waist attached to a belt pulley and an axle. Rod Moran writes, ‘He suicided in that beautiful tract of water which […] suffused his writing with memorable colour, texture and metaphysics.’

I was at the Claremont foreshore the Saturday my friend Jono died. I only found out later that it was also the place Griff’s body was discovered. Their deaths have become intertwined in my mind, connected by water even though Jono didn’t drown.

It was a still day at the end of summer and there was a strong glare off the river. The kids were watching brown jellyfish and playing in the sand. I was thinking about how I should text Jono, make sure he was still okay. I’ll do it later, I told myself. I was in a languid mood; everything seemed as unhurried as the drifting movements of those jellyfish. Back home in the afternoon, just as I was getting the kids into their bathers, he emailed me a brief message and I wrote back quickly, thinking he meant he was doing well. He killed himself while we were taking our long afternoon swim in the pool; his wife called me in the evening, while I was running a bath for the kids. He was forty-one; Griff was thirty-nine. It’s a dangerous season of life.

‘The weight was not touching the river bottom’, one newspaper reported of Griff in 1969, ‘and police believed it could have drifted into the pen’ (‘Poet’s Body’). But where did it drift from? Not Cottesloe Beach. I find myself trying to reconstruct Griff’s last hours. It’s a four kilometre walk from the beach to the river, not too arduous, but certainly not possible with a chain and weights. Did he park in Cottesloe to mislead the search? Had he already dropped off the chain and weights? Was he contemplating a trip, instead, and that’s why he packed the clothes?

Of course, these questions about the specifics of his death miss the more significant question of why. Not even the people who knew him best had a good answer to that. ‘I think he suffered some kind of deep depression and mental collapse,’ said his mother. ‘I don’t know of anything in particular that might have triggered it. And I don’t think I want to, but there was a previous unsuccessful attempt’ (Moran). The author Dorothy Hewett had seen him at a party about three weeks earlier and he seemed ‘undisturbed’ and ‘enthusiastic about projected works’ (‘Poet’s Death’).

5. Karrakatta Cemetery

Karrakatta Cemetery, the penultimate station on the memorial trail, is an hour’s walk along the railway line from Griff’s family home. His memorial plaque sits in the Garden of Remembrance, quite hidden at the back of a chapel. His plaque faces the air conditioning units. It’s a small, square metal plaque, set in a concrete block and using the standard wording: ‘In loving memory of Griffith Wynne Watkins.’ Next to his plaque is one for his father, who died in 1983; his mother’s plaque is in the same garden but on the other side. ‘For myself,’ his mother said toward the end of her life, ‘I don’t believe in death. I feel Griff is never far away from me’ (Moran).

In The Pleasure Bird, Brenton attends his friend’s funeral at Karrakatta at the crematorium chapel, once a landmark but razed in the 1980s. ‘He thought of him squashed up inside that box … not one thought in his head, already becoming a memory.’ Brenton thought of the fates of bodies very specifically. ‘He walked down the road to the cemetery gates, picturing Jack’s body burning in the oven like a rag doll, jack-knifing up with the intense heat … the disintegration of what had once been a man to powder’ (161). From this passage, I would guess Griff would have preferred burial—but that has its own horrors.

You can hear the train from your plaque, Griff—the same line you grew up on. And there are rose bushes in the garden. They are not blooming when I visit, but I’d like to think they do some times.

6. Murdoch University Special Collections

The Griff Watkins Memorial Trail ends at Murdoch University, an institution that did not exist in his lifetime. It is located down the freeway, far south from his familiar part of Perth. With the blessing of Griff’s mother, Kate, one of his poet friends, Peter Jeffery, edited a collection of Griff’s shorter writings, published in 1990 as God in the Afternoon. Peter was an academic at Murdoch and deposited Griff’s literary papers with the university library at the turn of the century.

The bulk of the collection is manuscripts. There are no diaries and most of the letters are his diligently collected correspondence about submissions and applications. It was probably inconceivable to Griff or his mother that his life might be of as much interest as his writings to someone like me. He wrote determinedly through his twenties and thirties, hundreds of poems and short stories and at least two unpublished novels. Peter sifted faithfully through Griff’s literary remains to produce God in the Afternoon. There are many profound moments in the collection, beautiful scenes, resonant lines of poetry, strange insights into life. One of the poems, ‘Heatwave’, drew me to Griff in the first place with its Audenesque panorama of a sweltering Perth day, flitting across newspaper offices, the lock-up, the zoo and along the river to the coast and the suburbs. Yet I find the collection a difficult and unsatisfying read. It is a showcase that doesn’t cohere, the folio of a writer interrupted. A reader’s report on an unpublished collection of Griff’s stories seems apt, ‘This is, by the look of it, a pretty awkward proposition but there is an artist kicking for his life among these pages’ (Reader’s report). In The Pleasure Bird, Brenton believes he can never emulate the success of the titular painting. ‘With that painting I pulled off the magic for the first and last time… The magic of matching my performance to my aspiration’ (208). Peter Jeffery writes that Griff’s ‘confidence was severely shaken’ when his follow-up novel, ‘Midas Land’, was rejected. ‘From this point on his writing faltered and his creative stamina flagged’ (251-2).

According to a letter to Griff’s parents preserved in his papers, in 1970 the Griffith Watkins Memorial Award was established. Touchingly, it was an idea launched by the school prefects at Tuart Hill Senior High School, where Griff had taught for many years. It was supported by teachers and the P&C. They raised $250 and deposited it in the bank, with the interest to be used for the prize each year. ‘I can assure you that the parents, teachers, and students have the greatest pleasure in perpetuating the memory of Griff in this way,’ wrote the principal. ‘We all hope that this will give both of you consolation in the years to come. We too have missed Griff’ (Clough).

How long did the prefects envision the memorial award lasting? Probably into the far-flung future, such would have been the intensity of feeling. But Tuart Hill Senior High School became Tuart College in 1982, a place for mature age students to complete year 11 and 12, and then it closed altogether in 2019. Somewhere along the line, Griff’s memorial award was forgotten.

When God in the Afternoon came out in 1990, Griff had been dead 20 years. A lot of people remembered him. I think it must have seemed to his mother, Kate, to be the beginning of a renaissance for her talented son. She was 80 years old then and had lived long enough for him to finally be recognised again. From that perspective, her death in 1998 came at the right time, before she could know that he was likely sinking back into obscurity.

But Griff isn’t completely forgotten yet. His poems pop up in anthologies; he has been mentioned in recent biographies of Gerald Glaskin, Randolph Stow and—unflatteringly—Gwen Harwood. His afterlife continues. But I hold this in tension with the clear-eyed pessimism of Julian Barnes, addressing his book’s final reader—for there must be one. ‘Even the greatest art’s triumph over death is risibly temporary’ (205). Memorial trails become overgrown with weeds, plaques are stolen or removed for redevelopment, trail guides get too old and no-one steps up to replace them. But while a trail exists, it is an act of remembering in a forgetful world, and that in itself is important.

Notes

Barnes, Julian. Nothing to Be Frightened Of. London: Jonathan Cape, 2008.

Clough, John. Letter to Mr and Mrs K.W. Watkins, 11 August 1970. Griff Watkins Collection, QB 26, Special Collections, Geoffrey Bolton Library, Murdoch, Western Australia.

Jeffery, Peter. ‘Afterword’ in Griffith Watkins, God in the Afternoon. Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1990. 250-256.

Kotai-Ewers, Patricia. The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its Role in the Cultural Life of Perth. 2013. Murdoch U, PhD dissertation, https://researchportal.murdoch.edu.au/esploro/outputs/991005544793807891.

Moran, Rod. ‘He Went to Die in the Swan’. The West Australian, Big Weekend, 16 June 1990, 9.

‘Poet’s Body Chained In River’. Newspaper clipping from unknown source, 15 September 1969. Privately held.

‘Poet’s Death Surprises His Friends’. The West Australian, 15 September 1969, 8.

Reader’s report on Griffith Watkins’ short stories. Date unknown. Griff Watkins Collection, QB 26, Special Collections, Geoffrey Bolton Library, Murdoch, Western Australia.

Watkin, Griffith. Application for University of Melbourne Standford Writing Program Scholarship. 1961. Griff Watkins Collection, QB 26, Special Collections, Geoffrey Bolton Library, Murdoch, Western Australia.

____‘Heatwave’. God in the Afternoon. Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1990. 83-86.

____ The Pleasure Bird. London: Longmans, 1967.

____ Typescript of poem Swanbourne. Date unknown. Griff Watkins Collection, QB 26, Special Collections, Geoffrey Bolton Library, Murdoch, Western Australia.

This is a beautiful tribute Nathan. I am one of Mary and Pip’s sisters, and Betty Brennan’s daughter. I vividly remember Griff visiting us when we lived in Kalgoorlie for three years when I was a child. He was such an exciting visitor for kids; the motorbike, the joking and cheerful playfulness. Mum and Dad were both so fond of him. Mum took the photo of him on his motorbike.

Remembering him and his talent, as you have done so warmly here, is so very much appreciated. I will buy a copy of The Pleasure Bird and read it soon!

With warm regards, Lucy Brennan-Jones

LikeLike

Wonderful to hear from you, Lucy, and another living connection to Griff! Thanks for reading.

LikeLike