Tags

Paul Auster has died. He is my favourite novelist. Being of a morbid disposition, I’ve been imagining this day for many years and now it’s true. I’ve been reading him for 25 years. Appropriately, there’s two versions in my memory of how I found him. In one version, I remember roaming the shelves of the Murdoch University library as a first year, picking books off the shelf serendipitously – which is not quite randomly – and once I picked up one of his books – perhaps Leviathan – and was hooked. In the other version, it was through my creative writing class I discovered him, an extract from The Invention of Solitude which I loved. Either way, I took out the Invention of Solitude after that and halfway through, I accidentally left it on a bench at the Perth Busport and had to pay $100 for a replacement (they did not replace it) and be reprimanded by a librarian. It was some years before I got to finish reading that beautiful memoir.

Moon Palace is my favourite book of his. It’s tied up to memories of Mitchell, who was my best friend then and whom, sadly, I have lost contact with. He was at Murdoch then, too, and we lived together for a semester and talked about Auster a lot and we were MS Fogg and David Zimmer. I wrote about Moon Palace here. I’m inarticulate when it comes to why I love Auster and I cannot explain what kind of books he writes to people. He reflects on chance and the process of making meaning from a life, the strange projects people undertake, their obsessions. He writes in transparent, simple prose which I find beautiful. It’s his early work I love best, but the two memoirs he produced a decade ago, Winter Diary and Report from the Interior are superb.

Here is a mystery: his penultimate book is a biography of Stephen Crane, Burning Boy. It gives me some comfort about the meaningfulness of biography that a fiction writer at the end of his life thought the story of someone else’s life worth devoting his time to. (This stems from a lingering uneasiness about my turn away from fiction to biography.) I haven’t read it yet – indeed, it’s nearly the only book of his I haven’t read – and I think I might be too sad about him to read it for some time.

In 2008, Auster was speaking at the Adelaide Writers’ Festival and I flew over to hear him. I wrote a post about it at the time:

I did not have a coffee with Paul Auster. I did not shake hands with Paul Auster. I didn’t even really have a conversation with him. But I went to Adelaide and heard him speak (I was just out of the tent in the sun and he was very small but distinguishable) and he was wise, cynical yet generous, amusing and weathered, just as I imagined and hoped for.

And I did exchange a few words with him.

I was waiting in the autograph line wondering what I could say to a man who I had spent so many hours with and who had been so important to me. In the end the exchange went like this:

NH: ‘You’re my favourite writer, Mr Auster – it’s an honour to hear you speak.’

PA: ‘Well thank you. Thank you reading for my books.’

(Paul Auster indecipherably scribbles in my battered copy of Moon Palace.)

NH: ‘In my new novel one of the characters reads Moon Palace.’

PA (looking surprised): ‘Really? Well thank you.’

What happened then? Did he move onto the next person or did I walk away, spoiling a promising opening because there were a thousand people behind me waiting in the hot sun? I don’t know.

The reality is that you can’t hope to know a writer in ‘real life’ with any of the intimacy or depth that you know him or her through their books. It’s just not possible. It’s the wonder of reading and writing. Auster even said something to this effect at some stage, or I think he did.

There was a time when I would have thought of a witty or controversial or brilliant question to ask and I would have asked it, and I would have waited by the tent for hours, and I would have pushed my way into talking to Auster. But I’m 27 now, as of yesterday, and I’m old and shy. I’m mistrustful of people who push their way forward and I’m sick of egos.

I was glad I went, because I had to and because I enjoyed it, and yet it was in an important sense exactly as I feared.

gosh, what a shock. I’m so sorry. I know well that feeling, that I experienced when we lost Hilary Mantel and Gabrielle Carey. They are loved ones who’ve brought us joy and growth. And fun! I loved Leviathan and Winter Journal. Thanks for sharing your memories of him.

LikeLike

Oh, it’s been a sad 12 months. I think we should give ourselves permission to grieve our beloved authors, even if it’s a one-way relationship. I’m glad you liked Leviathan, I don’t hear enough about it! I recently read of the parallels to the unabomber, which I missed previously.

LikeLike

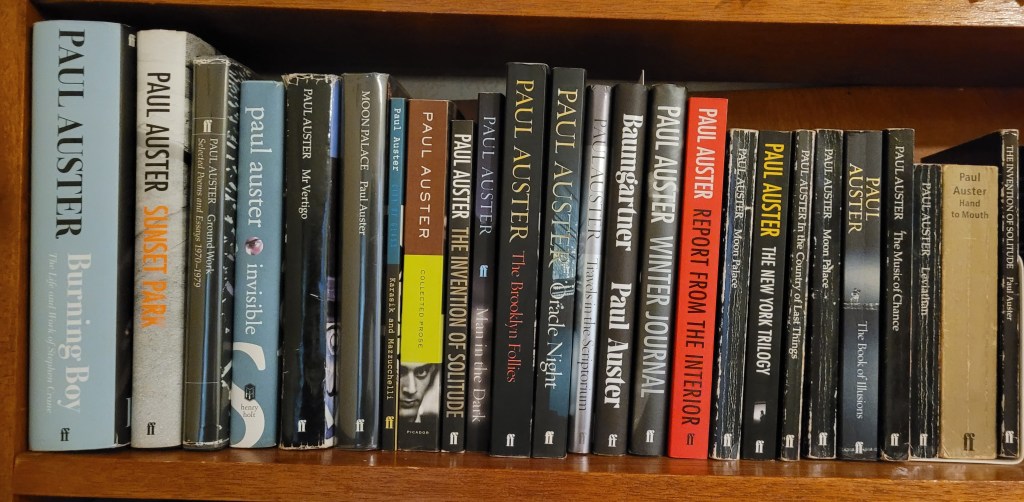

Oh that’s so sad. Paul Auster is among my favourite writers too. I haven’t read Leviathan but adored The Brooklyn Follies – with Nathan as a character! – and Invisible. His writing is incredible, as is your collection – very impressive. What an amazing body of work. I’m glad you got to meet him 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you Linda – I should give Brooklyn Follies another read!

LikeLike

I haven’t read Paul Auster, although he’s been on my list for a long time! Now I’ll have to get cracking.

But, Nathan, I’m finding it hard to believe in your ‘morbid disposition’! Oh dear. And yet a fan of KSP, who, in my opinion, was an eternal optimist with the sunniest disposition imaginable! Denise

LikeLike

Morbid in that I think of death a lot, but that makes life more precious. KSP certainly showed how to have hope in the darkest times.

LikeLike