Hector Harrison (1902-1978) was a prominent Presbyterian minister who led St Andrew’s Church in Canberra from 1940 until his death. He was friendly with Prime Minister John Curtin and Fred Whitlam, father of Gough Whitlam, who was a member of his congregation. There’s a striking scene from Harrison’s oral history at the National Library recounted in Dr Margaret McLeod’s new biography: Harrison is giving Whitlam senior a lift home from the 4th July celebrations at the American Embassy in 1945 and Whitlam reveals that the editor of the Canberra Times had just told him John Curtin wouldn’t last the night. Harrison walked across the paddocks to the Lodge and was, eventually, admitted to see Curtin, hours before his death. At Curtin’s request, Harrison conducted the funeral.

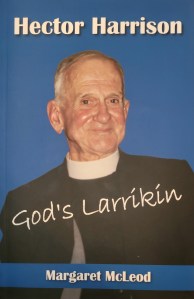

McLeod’s biography of Harrison is a project sparked by her deep admiration for him when she came to know him in the 1970s. Hector Harrison: God’s Larrikin is a comprehensive biography of 550 pages, tracing his life and career across all its stages. McLeod writes, ‘It was my aim to rouse these memories in an attempt to capture the essence of Hector Harrison, his boyhood development and influences; the emergence of the thoughtful and intelligent young man who determined he would devote his life to God’s work; the torturous journey to Presbyterianism; the challenges of his early ministry; the energetic and influential man of middle age; and the equally energetic and opinionated elder statesman.’ (22) The book is meticulously researched; Harrison’s papers at NLA are a major source, supplemented by extensive oral history interviews, newspaper sources, and other archival sources.

I was interested to read of Harrison’s life and ministry in Canberra in the war years; this biography paints a picture of life in the capital at that time that complements the memoirs and biographies of politicians and journalists I’ve previously read. There is also a whole chapter on Harrison’s friendship with Curtin. Harrison, who grew up in Northam like Hugo Throssell, had been minister at St Aiden’s in the Perth suburb of Claremont while Curtin was living in neighbouring Cottesloe; they didn’t actually meet until they were both in Canberra, but it was a strong point of connection. (I go past the beautiful stone church of St Aiden’s many times a week.) The question of Curtin and religion is a complicated one, with few hints to go on. The memo prepared by Curtin’s private secretary at Harrison’s request is one of the key sources, but in one sense only reveals the questions and gaps. No one wanted to talk directly about faith with the prime minister. McLeod interprets this and other sources with appropriate caution.

The biography incorporates unflattering aspects of Harrison’s character without defensiveness, such as a quote from his daughter, Claire Lupton: ‘Democracy was an unheard of word for Dad in regards to the church, he would override anyone.’ (19) (It was a neat discovery to learn that Professor Deborah Lupton, one of the voices of clarity about the ongoing covid pandemic who I follow on Twitter, is Harrison’s granddaughter.) An sad note is struck in the foreword by Harrison’s son, Ian, who writes candidly, ‘If the Rev. Hector was a family man, it was principally his parishioners who were his family. In the evenings he was usually out visiting them at home unannounced … If at home, he was usually working in his study.’ (2) He goes on to conclude that McLeod ‘knew him much better than I did and, through reading her scholarly account of his life and career, my knowledge has been deeply enriched.’ (3) I feel the words could have been written about my own grandfather, an Anglican clergyman a little younger than Harrison who was beloved by hundreds across the state – focused like him on pastoral care – but who was, sadly, not present enough for his own family. Of course, absent men over-committing themselves to work was not limited to ministers then or now; John Curtin’s children, for example, remarked how rarely he was at home. It is a way of life which takes a great toll on families.

God’s Larrikin can be purchased for $40 plus postage from InHouse Publishing here.

Tried to leave comment, but WP said “can’t be posted”

LikeLike

I’ll try again

My Nana was a Canberra Presbyterian, from the 1940s to 1970s so maybe a parishioner.

Looking up the family history I couldn’t see about her church but came on this in the section Holloways in Victoria (not related): the Rt Hon EJ Holloway, born in 1881, Minister for Social Services in the Curtin government of 1941-45 (I met his son’s widow, aged 88, just before she died recently [ie, 1999])”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think your Nana would certainly have known him! I wondered if you were related to EJ Holloway. He was a key ally of Curtin’s, I believe.

LikeLike

Dad found about 20 mentions of Holloways in Victoria in the 1800s, the most famous being station owners near Swan Hill with whom Bourke & Wills stayed on their way north.

Our Holloways come from Qld. Dad’s father moved the family to Canberra when he got a job in the public service, then to Melbourne during WWII, which is how Dad ended up Victorian. Sorry none of this helps you with Curtin. Hope it’s going well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your family has Australia well covered! I’m making some progress on Curtin. It’s a patchwork – I’m doing 1944 at the moment.

LikeLike