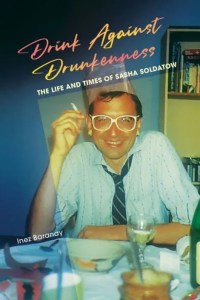

Drink Against Drunkenness: The Life and Times of Sasha Soldatow Inez Baranay 2022, 508pp, RRP $39.99.

Last year I chanced upon a newspaper clipping from 1990 about the writer and activist Sasha Soldatow (1947-2006) suing the Australia Council over him not being awarded a fellowship despite many applications. It led me to David Marr’s intriguing obituary for the man. ‘To fall in with Sasha at this time was a life-shaking experience. He marched and drank under the banner of Liberty… The deal he offered was this: place yourself in my hands, and I will set you free.’ I commented on Twitter that someone should write Soldatow’s biography. It turns out someone had been! Drink Against Drunkenness: The Life and Times of Sasha Soldatow is a labour of love by his friend, the writer Inez Baranay, author of 14 previous books.

The book lives up to its subtitle of depicting the ‘times’ Soldatow lived through. Drink Against Drunkenness is a valuable chronicle of a milieu – the underground publications, the share-houses and squats and other living arrangements of the 1970s, the campaigns and controversies. Baranay lets the participants speak, quoting from in depth interviews with them, supplemented where possible with contemperaneous written sources.

Sources are a challenge in any biography. Baranay’s particular challenge is that Soldatow didn’t tend to record his inner life. His diaries are full of appointments but only occasional moments of introspection. ‘For someone so certain of a future biographer, he rarely recorded his funniest jokes, wittiest lines, the most salacious gossip passed on.’ (p. 164)

Soldatow knew a remarkable range of people. His contemporaries in the gay community, David Marr and Dennis Altman, make appearences. The historian Judith Brett was a friend and her memories of him make a significant contribution to the portrait of him. Future high court judge Viriginia Bell once shared a house with him; ‘he had no money and we had no money but he’d expect us to subsidise his lifestyle as a poet’, she remembers, and it’s the accumulation of memories like this that make me suspect I would have found Soldatow insufferable. (p. 118) Soldatow’s lover Mark McLeod was good friends with the novelist Thea Astley and Soldatow pestered him for a meeting; staying with her for a weekend Soldatow and Astley ‘hated one another instantly’. (p. 174) The biography is full of intriguing stories of Soldatow’s outrageous behaviour and madcap schemes, as well as his wide-ranging and unpredictable publications, including Jump Cuts: An Autobiography (1996), written with his protege Christos Tsiolkas.

Late in the book, Berenay considers ‘That Topic’ – paedophilia in Soldatow’s thinking. I was horrified to learn he argued children should be able to consent to sex and for many, including me, the revelation will cast a pall over their perception of his character. For him, it was a philosophical conviction about liberty rather than something he is ever known to have done. Baranay is uncomfortable too, and hopes that the better understanding we have today of the deep trauma of child sexual abuse and the uneven power dynamic would lead Soldatow to a different conclusion.

Reading this book, I’m left with a sense of the biographer’s great generosity both to the past and to posterity in recording Soldatow’s life, and, in the background, the poignant story of a generation and its misadventures and partially-filled ambitions over the decades.

I would have found him insufferable too.

Back in the 80s, we used to have some friends who were too deeply into sustainable living to pollute themselves by having a car. So we and our other friends drove them around everywhere instead, with no contribution to the fossil fuel industry, of course. They had to remain pure. I don’t think we were the first to get fed up and refuse to be their unpaid taxi service. We were certainly relieved when they got huffy and abandoned the friendship!

LikeLike

Oh no, got to make actual sacrifices yourself if you want to be ‘pure’!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never heard of Sasha Soldatow, Nathan, so thanks for introducing him. He sounds interesting but not someone I’d care to know or read about, so don’t think I’ll bother with the biography! Denise

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Denise, a true character and an acquired taste, perhaps!

LikeLike

Thanks for the review, Nathan. It’s true that many found Sasha insufferable but over 50 interviews with people who knew him were a testament also to his charm, generosity, honesty, courage, wit, and literary mentorship. His story, as you indicate, is also of his generation and many social movements. Sadly his story is also one of decline.

LikeLike